- Filed under: Uncategorized

4 Types Of Hiatal Hernia

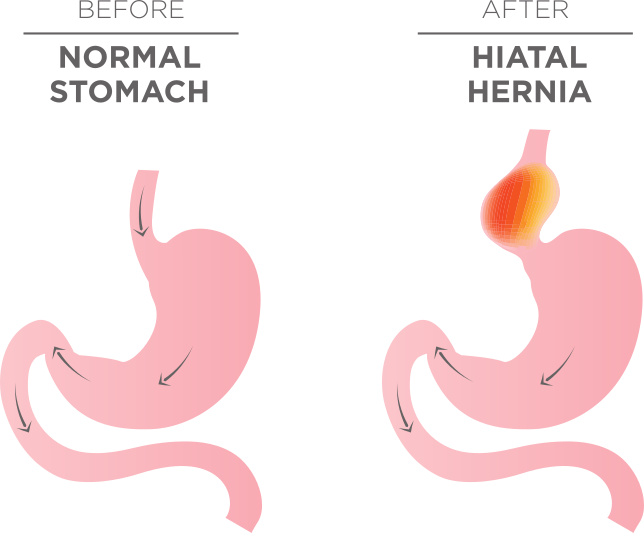

Hiatal hernia (HH) is the migration of any abdominal organ, usually the stomach, above the diaphragm into the chest. Although HH can be a major contributing factor in persons with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), not everyone with a hernia will have GERD and not all hernias require treatment. There are four types (TI-IV) of hiatal hernia.

Type I

Ninety-five percent of hiatal hernias are type I or sliding hiatal hernias which involve migration of the gastroesophageal junction into the chest. Type I sliding hiatal hernias are extremely common. They result from laxity of the ligaments that connect the lower esophagus to the diaphragm. The lower esophagus and upper stomach are located in a dynamic region with constant movement and pressure variation with swallowing and breathing.

The esophagus shortens nearly 2cm every time we swallow and we swallow and breathe thousands of times each day. The constant movement puts tension on the ligaments connecting the diaphragm to the stomach and results in laxity over time. The laxity increases with the tens of billions of swallows and hundreds of billions of breaths over a lifetime. This predisposes an individual to the development of TI HH with advancing age. Other risk factors for TI HH include obesity, race (Caucasian), weight lifting, and genetics.

Type I & GERD

Over 30% of the population without a history of GERD has evidence of TI hiatal hernia. Small Type I HH frequently alternate through states of herniation and reduction. This can make the diagnosis of small hiatal hernia challenging and even arbitrary at times.

Thus, the presence of TI HH can be viewed as ubiquitous and its presence does not imply the presence of clinical reflux disease. It is essential for the clinician to differentiate hernias that are innocuous bystanders from those that are intimately involved in an individual’s reflux disease. Hernias that are large (>4cm) and those that do not reduce on endoscopy or swallowing fluoroscopy, are more likely associated with incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, high grade-esophagitis, peptic stricture, Barrett’s metaplasia, and profound GERD symptoms such as dysphagia, intractable pain, and chronic cough.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of HH can be made by using videofluroscopic esophagram (VFE), esophageal endoscopy and high-resolution manometry (HRM). Although the majority of Type I hernias are small and do not require treatment, HH does result in lower esophageal sphincter incompetence and results in a greater propensity for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). People with hiatal hernia are more likely to have symptomatic GERD and the greater the size of the hernia, the greater the severity of the GERD.

Type II

The Type II hiatal hernia is a paraesophageal hiatal hernia. The gastroesophageal junction is contained at its physiologic location at or below the diaphragmatic hiatus and the gastric fundus herniates through a localized defect in the diaphragm.

TII HH are less likely associated with lower esophageal sphincter incompetence and GERD than Type I hernias. The primary concern for TII HH is the propensity of the herniated stomach to rotate and develop strangulation. This may result in hemorrhage, perforation, and ischemia (tissue death). Because of the normal location of the gastroesophageal junction, TII HH can be difficult to visualize on both endoscopy and fluoroscopy. True TII hiatal hernia is exceedingly rare. The majority of paraesophageal hiatal hernias are of the mixed variety (Type III).

Type III

A TIII hiatal hernia is a paraesophageal hiatal hernia that is a combination of a Type I and II HH. With a TIII HH, the gastroesophageal junction is herniated above the diaphragm into the chest with a large portion of the fundus and gastric body. TIII hiatal hernia are thought to begin as Type II hernias that cause progressive relaxation of the PEL over time and ultimate herniation of the gastroesophageal junction. Unlike TII hiatal hernias, Type III hernias are associated with significant gastroesophageal reflux and its related complications. The large defect in the diaphragm makes them relatively easy to identify on endoscopy and fluoroscopy.

Type IV

A Type IV hiatal hernia is a large paraesophageal hiatal hernia that is associated with herniation of other abdominal organs such as the small and large bowel, pancreas, or spleen. These hernias may be asymptomatic or may cause symptoms similar to other large hernias such as epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting, swallowing difficulty, and gastroesophageal reflux. Bowel obstruction and ischemia are rare complications.

Treatment of Hiatal Hernia

Small hiatal hernias are frequently asymptomatic. Large hernias, however, are more likely associated with severe symptoms and mucosal complications of GERD (esophagitis, stricture. Barrett’s). Large hernias promote reflux by weakening the lower esophageal sphincter and by reducing esophageal clearance of regurgitated gastric contents. Secondary esophageal peristalsis is essential at clearing the esophagus of refluxate. Hernias alter this ability and result in prolonged acid contact times in the esophagus. This delayed clearance and prolonged acid exposure is more likely to cause both symptoms and tissue damage.

Small hernias can often be successfully treated with conservative measures. These treatments include behavioral modifications such as avoiding tight-fitting clothing and elevating the head of bed to 35 degrees during sleep, diet and exercise, antacids and alginate therapy. Medications such as H2 receptor antagonists (e.g. Pepcid) or proton pump inhibitors (e.g. Prilosec) may be required in more severe cases.

Large HH can also be treated with these measures, although patients with large hernias are more likely to have reflux that does not respond to medication and require surgical repair. Surgical repair (reduction) of the hernia is often combined with a fundoplication. Fundoplication is a procedure where part of the stomach is wrapped around the lower part of the esophagus to tighten the lower esophageal sphincter surgically. This operation is usually performed through endoscopes placed through small ports in the stomach (laparoscopy).

If you have a hiatal hernia that is causing reflux, check out our blog for more information on managing gastric reflux: https://refluxgourmet.com/introduction-to-gastric-reflux/